The Missed Education: What Schools Already Knew

The Untapped Power of a Billion School Conversations

Every day, millions of conversations flow between parents and schools—logistics about missed buses and sick days, updates about academic breakthroughs and stumbles, questions about homework, concerns about behavior, and thoughtful exchanges about a student’s passion.

Hidden in these exchanges lies an unprecedented repository of knowledge - knowledge flowing from every kind of family that makes up our school communities: newly arrived immigrant families navigating an unfamiliar system, multi-generational households balancing complex schedules, single parents working multiple jobs, blended families coordinating across households. Families of every socioeconomic background, culture, and configuration. These conversations reveal how different communities interact with the school system, what creates barriers and what creates opportunities, where programs succeed and where they fall short. They contain intimate insights into the daily challenges families face, and capture the worries, hopes, and dreams of the next generation.

Until now, analyzing these conversations at scale seemed impossibly complex. We've built institutions of learning that, through no fault of their own, haven't had the tools to learn from their own communities. New analytical tools, powered by artificial intelligence, are finally making it possible to learn from these millions of conversations.

The Knowledge Gap

Modern schools face a paradox: they're drowning in information while starving for insights. Every email, every message, every parent-teacher conference contains valuable knowledge about student needs, community concerns, and emerging challenges. But this knowledge remains largely inaccessible, trapped in thousands of isolated conversations that no human team could possibly analyze comprehensively. Consider just one large district like Los Angeles Unified: with 557,000 students having just one conversation every two weeks during the school year, that's over 10 million annually. Even if a team could somehow review one conversation per minute, working non-stop for 8 hours a day, it would take over 100 years to analyze a single year's worth of communications. And that's a conservative estimate that doesn't account for the multiple weekly exchanges many families have with teachers, administrators, and staff or the fact that more than 150 languages are spoken by students at LAUSD.

Traditional solutions fall short. Manual reviews can only sample a tiny fraction of communications. Basic metrics like response times or message volumes miss the deeper patterns - they can tell us how often people communicate but not what they're actually saying. A parent's five messages in a week might be counted, but their connection to a broader pattern of transportation barriers goes unseen. Statistical measures can show us that response times are slower in certain neighborhoods, but they can't reveal if families are struggling with language barriers or complex work schedules or the fact that the city changed a bus route. These approximations and averages, while useful for basic tracking, leave the actual substance of conversations - the challenges and needs of real families - completely unexplored.

Making the Invisible Visible

Every experienced educator carries deep insights about their community. They know which bus routes flood during storms, which homework policies work for families juggling multiple jobs, and how language barriers ripple through every aspect of school life. This understanding, built through thousands of daily interactions, has always been there. But it's remained trapped in individual observations and informal knowledge - powerful but isolated.

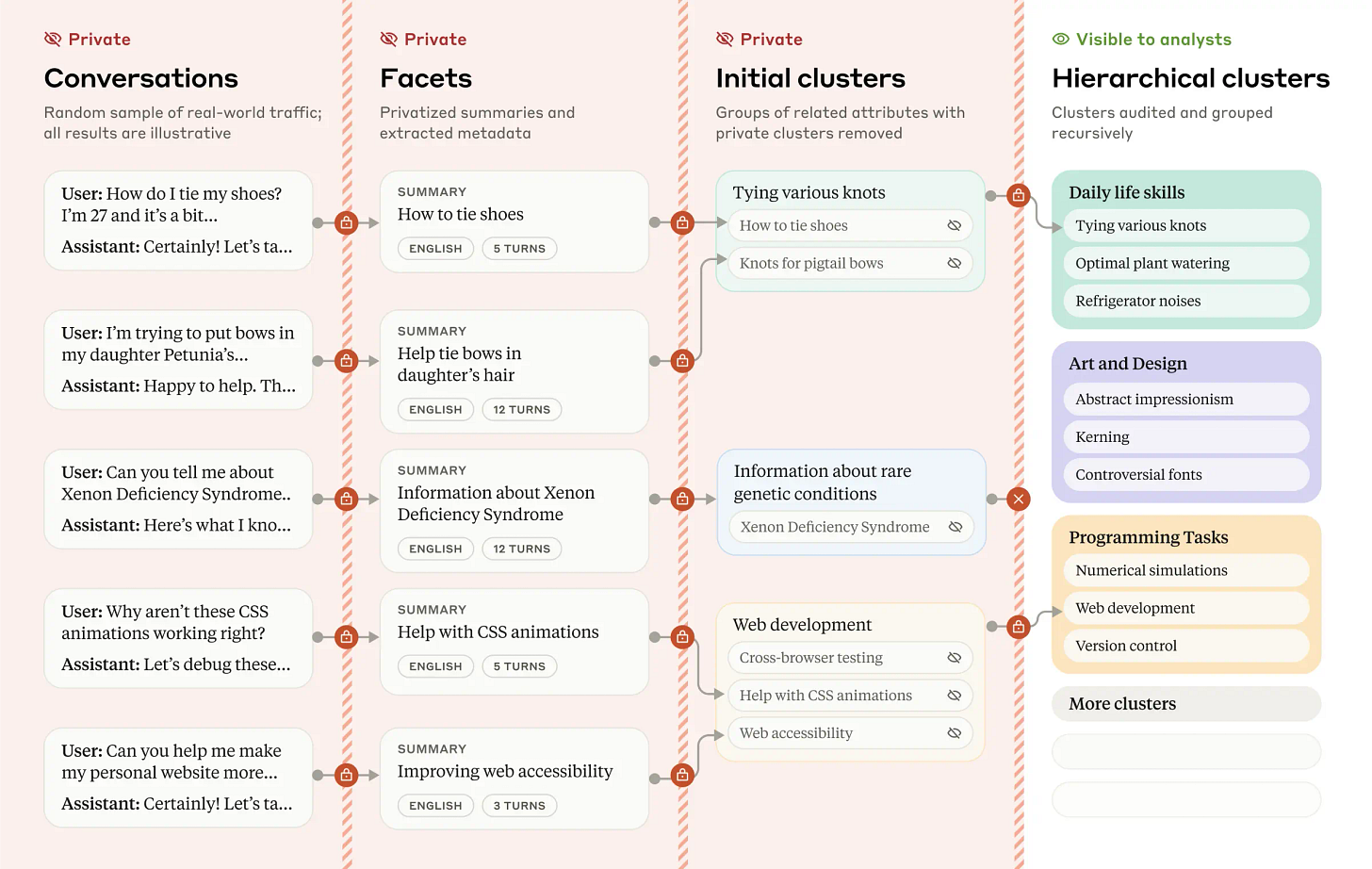

What if we could learn from every conversation happening across a school system? Recent advances in natural language processing have made it possible to understand patterns in millions of communications while preserving privacy. Tools like those developed by Anthropic demonstrate we can now analyze these conversations systematically and ethically.

When a principal notices transportation challenges on rainy days, they can now see that twenty other principals across the district are experiencing the same pattern—turning an observation into a statistic that demands attention. When teachers hear about assignment struggles, they can connect with colleagues district-wide to quantify the scale: not just three families in one classroom but three hundred across the system facing the same time constraints. When staff encounter language barriers, they can aggregate these experiences across schools to show precisely how many families face similar challenges with homework, events, and attendance communications—transforming individual cases into documented trends.

The technology to do this exists. But the real breakthrough isn't technical - it's about finally being able to learn systematically from the collective experience of our school communities. Instead of each educator working with their own slice of understanding, we can now surface patterns that validate and amplify their insights, turning individual observations into evidence for change.

Knowledge at Scale

Applying Anthropic’s Clio framework to School-Parent conversations.

Step 1: Listen at Scale (extracting key themes or facets)

Gather the conversations of families and educators.

Preserve the privacy of individual conversations while learning from their collective meaning.

What does it look like? Imagine if teachers wrote down a post-it-note-sized description of every conversation they had with families. "Parent called because bus was 30 minutes late." "Student absent - family's car broke down, no other way to get to school." "Parent can't make afternoon conference - works until 6pm and relies on school bus for child's transportation."

Step 2: Find the Common Threads (semantic embedding)

Notice which stories keep repeating across different families.

See how similar challenges show up in different ways.

What does it look like? Now imagine sorting through hundreds of these notes and adding colored tabs for different themes. You start noticing that many have multiple tabs - the same post-it might have red for transportation, yellow for attendance, and blue for work schedules. Patterns emerge that weren't visible when looking at each note individually.

Step 3: Map the Community Experience (dynamic clustering)

Group similar experiences to see the bigger picture.

Watch how different challenges connect and overlap.

What does it look like? Those colored tabs help you arrange the notes into clusters. You notice that almost every note about missed parent-teacher conferences (purple tab) also has tabs for work schedules (blue) and transportation (red). What looked like separate issues - attendance problems, missed conferences, after-school program participation - start revealing themselves as connected pieces of a larger transportation challenge.

Step 4: Turn Understanding into Solutions (pattern labeling)

Organize findings into clear, actionable insights.

Make patterns visible and accessible to education experts.

What does it look like? The analysis reveals clear patterns: certain neighborhoods show consistent transportation challenges, specific times of day create barriers for working families, language support needs follow distinct patterns. These insights are then shared with educators and administrators who understand how to apply this knowledge in their specific contexts.

Knowledge Creates Responsibility

Every principal knows when families are struggling to get their children to school. Every teacher understands which families can't make afternoon conferences because of work schedules. Every staff member sees how language barriers affect participation in school events. This understanding has always existed in the thousands of daily interactions between schools and families.

But when we can analyze these patterns systematically—when we can show that 40% of families in certain neighborhoods consistently miss afternoon meetings, or that attendance drops by 30% on rainy days in areas with limited bus service—individual observations become undeniable evidence. What was once informal knowledge becomes a clear imperative.

This transformation from intuition to evidence changes everything. When a principal can demonstrate how transportation challenges affect not just attendance but parent engagement, homework completion, and after-school participation, they have the tools to advocate for change. When teachers can show how different homework policies impact families across the district, they can shape more equitable practices. What educators have always known becomes visible, measurable, and actionable.

Knowledge makes us responsible. Once we can see these patterns clearly—once we can measure their impact on families and track their ripple effects through our communities—we can no longer look away. This isn't about placing new burdens on already-stretched schools. It's about finally having the tools to understand our communities deeply enough to serve them effectively.

The insights have always been there, in every conversation between families and schools. What's changing is our ability to learn from them systematically—and with that ability comes both opportunity and obligation.

Surfacing Hard Truths

When we analyze patterns in family-school communications at scale, we're likely to uncover systemic inequities that many would prefer to ignore. The data might reveal that certain communities consistently receive slower responses, or that their concerns are more often dismissed. It could show how language barriers create cascading effects - not just in direct communication, but in access to programs, participation in school events, and student support services.

These patterns might expose uncomfortable truths about how schools interact differently with families based on their socioeconomic status, primary language, or cultural background. We might find that what gets labeled as "parent disengagement" in some communities is actually a reflection of institutional barriers - like scheduling parent-teacher conferences during work hours, or having insufficient translation services.

The system could also reveal biases in how schools interpret and respond to similar situations across different communities. A request for academic support might be treated as "proactive parent involvement" in one neighborhood but as "excessive demands" in another. Behavioral concerns might trigger supportive interventions for some students while leading to disciplinary actions for others.

These insights aren't just data points - they're evidence of systemic inequities that need to be addressed. But surfacing these patterns is only valuable if we're prepared to act on what we learn, even when it challenges our assumptions or requires difficult changes to longstanding practices.

The Responsibility of Understanding

When we organize thousands of conversations into patterns and trends, we're doing more than just analyzing data - we're shaping how schools see their communities. Every choice about what makes something important, what counts as normal, what deserves immediate attention - these decisions influence how educational leaders understand and respond to family needs.

This framework could transform how schools serve their communities. But with that potential comes responsibility. The patterns we find will reflect our own biases about what matters and what doesn't. Some family experiences won't fit our categories. Some crucial needs might slip through the cracks of our classifications. And the communities most often overlooked by educational systems are the ones most likely to be missed by our patterns.

These aren't just technical limitations; they're fundamental challenges in any attempt to understand human experiences at scale. We're not aiming for perfect understanding. We're trying to help schools learn from their communities more effectively while staying aware of what might be missing. Success means finding useful patterns while never forgetting that behind each data point is a unique family story that might not fit neatly into our framework.

Knowledge in Community

Every day, millions of conversations between families and schools capture how communities everywhere support their children's education. Until now, these conversations have remained fragmented - valuable knowledge scattered across countless interactions, emails, and meetings in every language and culture.

This isn't just about making sense of data - it's about honoring the experiences of every family trying to help their children succeed. It's about taking the understanding that already exists in our schools and giving it the structure and scale to drive real change. And most importantly, it's about doing this work carefully and ethically, always remembering that behind every pattern we find are real families with unique stories.

We finally have tools powerful enough to learn from every family's experience, across languages and cultures. Used thoughtfully, they could help schools everywhere better serve their communities - not by replacing human understanding, but by giving it the scale and structure it deserves.